Houston’s Astrodome Was a Vision of the Future. It’s Past Its Prime.

By J. David Goodman Houston bureau chief, The New York Times | July 26, 2025 | Original Article

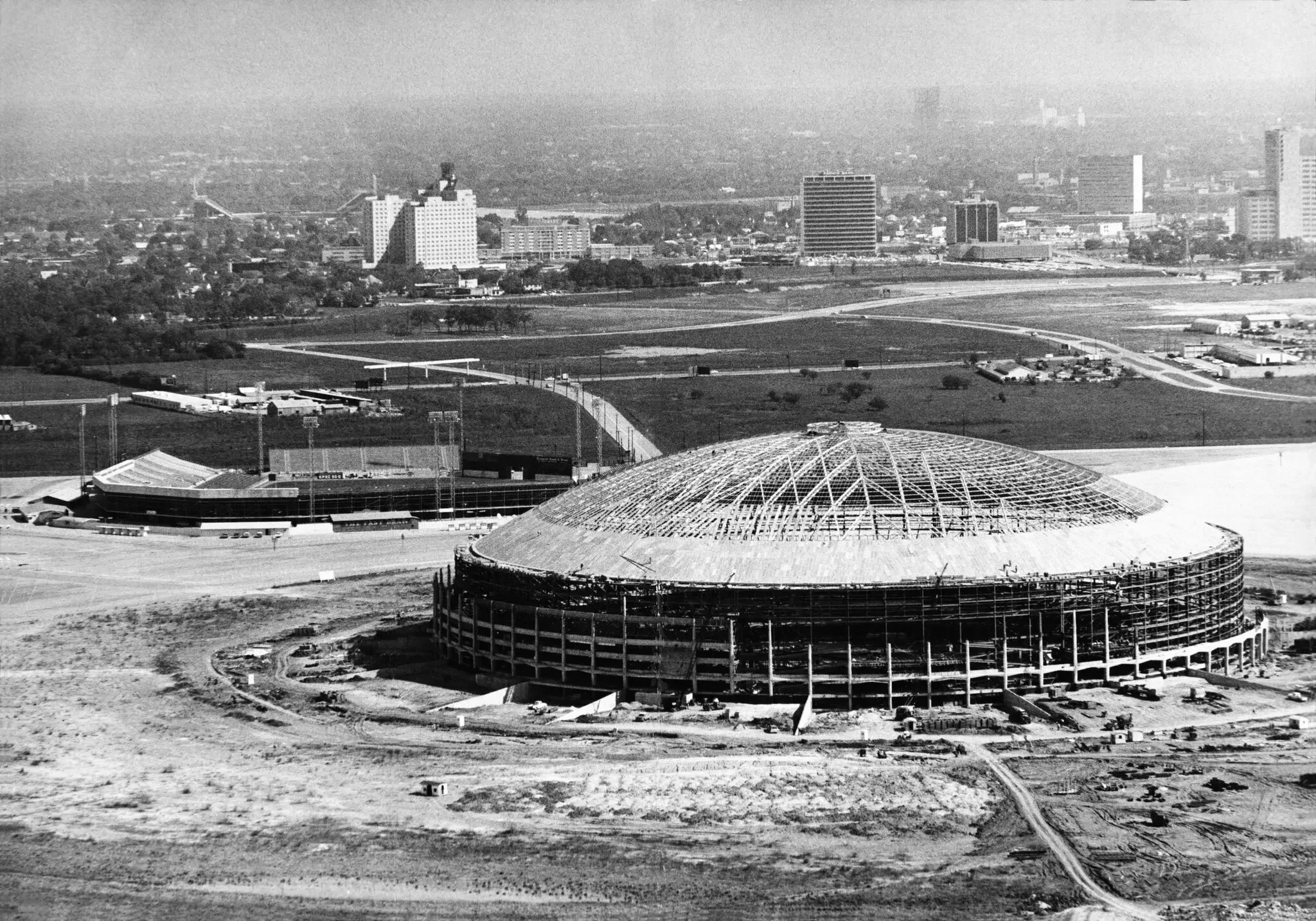

The Astrodome while it was under construction in 1964.

Credit: Sam C. Pierson/Houston Chronicle, via Associated Press

There are not many iconic structures in Houston, a city more famous for how it spreads out than what it builds up. The Astrodome is the exception.

Never mind that no baseball or football has been played there in a quarter-century, or that music hasn’t echoed through its cavernous circumference since George Strait’s voice twanged through the upper decks in 2002.

It opened as the nation’s first domed stadium in 1965 with a constellation of astronauts hurling a meteor shower of ceremonial pitches. The landmark still exerts a hold over Houston’s collective memory — a bygone vision of a space-age future in a city not inclined toward nostalgia.

But what to do with the hulking structure has raised uncomfortable questions that many American cities have confronted: What is a place without its best-known building and what is it worth to save?

Other cities have wrestled with what to do with the cherished but fading emblems of earlier eras, like a 1964 World’s Fair pavilion in Queens, New York, an Olympic Stadium in Montreal or the Marine Stadium in Miami.

Proposals to destroy them bring emotional responses. But the idea of pouring public money into saving such structures — especially if they are controlled by local governments, like the Astrodome is — also draws howls.

It can be easier for political leaders to do nothing. And so many are left to sit. And sit.

“This is not an overstatement: The dome has really been the bane of my existence,” said Ed Emmett, who tried unsuccessfully to shepherd through a modest renovation plan for the Astrodome several years ago when he was the judge of Harris County, the government that controls the stadium and its surrounding park.

The latest plan to save the Astrodome involved converting it into a glittering arena and event space for about $1 billion, an initiative that was met mostly with indifference when it was unveiled by the nonprofit Astrodome Conservancy last fall.

Soon after, Harris County officials commissioned a new study to consider tearing it down, among other fates.

“As the years go on, those of us who spent time in there are dwindling and moving away,” said Craig Hlavaty, a freelance columnist and reporter in Houston with a tattoo of the stadium on his left calf. “It’s almost a monument to government inactivity and apathy at this point.”

The building, a state landmark, is listed in the National Register of Historic Places. It fell into disuse when the professional sports teams moved away, and has been closed and vacant so long that its basic systems no longer function. For years, almost no one has been allowed inside to see its most striking feature — the interlocking lamella structure and skylights of its towering roof.

“I have yet to meet a person who goes into the Astrodome for the first time and doesn’t go, ‘Wow!’” said Mike Acosta, a historian for the Houston Astros and a proponent of saving the Astrodome, where he attended games growing up. “It’s like looking at a piece of art.”

On a recent visit, the ceiling dazzled in the late morning sun, soaring over the cavernous expanse and retaining its power to impress.

But the emptiness was also striking.

Most of the seats were removed long ago, auctioned to Houstonians and other fans to adorn living rooms, sports bars or the waiting areas of dentists’ offices around town. Those that remain, with their Texas-shaped number markings, wrap around a section of the balcony in dusty bands of yellow, orange, red and blue. Artificial turf sits in rolls on what had been the field, now a storage area.

“I have four pieces of Astro turf stitched up on my wall. I have Astrodome seats,” said Mr. Hlavaty, who once wrote “caffeinated screeds about saving the dome.”

Over the years, there has been a range of proposals for what to do with the structure. Some have lacked imagination, like turning it into a massive hotel. Others have been fanciful, such as flooding it for naval battle re-enactments.

“You have 2.3 million people in the city of Houston, so you have 2.3 million ideas of what to do with the Astrodome,” said Ryan Slattery, who caused a stir when he was a University of Houston student with his idea to turn it into an open-air pavilion.

Part of the challenge is that the Astrodome sits in the middle of Harris County’s NRG Park, right next to NRG Stadium, home of the N.F.L.’s Houston Texans, and in the middle of the grounds for one of the city’s biggest annual events, the Houston Livestock Show and Rodeo.

Neither the Texans nor the rodeo have been particularly excited about efforts to save the old stadium. Neither have many Houstonians over the years.

In 2013, voters narrowly rejected a $217 million bond to repurpose the Astrodome. “It was defeated, but not by much,” said Phoebe Tudor, the chairwoman of the Astrodome Conservancy. “People to this day get confused and think, ‘Didn’t we vote to tear it down?’”

After that, Mr. Emmett, then the county judge, proposed a cheaper plan, without a bond, to fix up the building enough to allow people inside its main floor area.

“There’s no point in getting rid of it. It’s a fully paid-for building, and it’s structurally sound,” he said in a recent interview. “Having nine acres of covered space in Houston is a good idea.”

The county approved it, but a plan from a Republican county judge proved contentious. A Democratic state senator from Houston at the time, John Whitmire, tried to head off the effort in the State Legislature, saying any new plan should be presented to voters again. Mr. Whitmire, now the mayor of Houston, remains lukewarm. A spokeswoman said the Astrodome was “not a priority right now.”

Mr. Emmett’s plan ultimately died after he was defeated in 2018 by a progressive Democrat, Lina Hidalgo. He recalled urging Ms. Hidalgo, “Let the Astrodome plan go forward and blame me.”

Instead, he said, she canceled it.

Then in November, the conservancy released its new plan to transform the stadium into a multiuse destination with an arena, an elevated pedestrian boulevard, retail shops, restaurants and a hotel.

“The beauty of the Astrodome is that it is a large shell,” said Ryan LeVasseur, who has overseen major real estate projects in Houston and worked with the conservancy on its plan. “There are very few precedents for something like this. Frankly there is no precedent.”

Ultimately, the county must approve any renovation. Several officials have publicly and privately been skeptical of the new plan’s viability, citing the lack of private funding and the county’s budget deficit.

Rodney Ellis, a Democratic county commissioner, said that while the Astrodome has historical significance, the county had “other important and deserving priorities like criminal justice reform, flooding and housing.”

The county has also been negotiating with the Texans and the rodeo over a new long-term lease; both would rather see public money spent on improvements to the NRG stadium — now more than 20 years old — and to the rest of the park.

A spokeswoman said the rodeo remained focused on the “long-term viability of the facilities we actively use,” and was “eagerly awaiting” the results of the county’s Astrodome cost study, which a county spokeswoman said would come this fall. A representative for the Texans did not respond to requests for comment.

“If it has to get torn down, I’m sure I’ll be there like everybody else will be,” Mr. Hlavaty said. “I’m not going to chain myself to the building anymore. I’ve very much softened my enthusiasm for it. I just want a resolution.”